OverviewMarkov Decision ProcessDiscounted (Infinite-Horizon) MDPobjective, policies, and valuesBellman Consistency Equations for Stationary PoliciesBellman Optimality EquationsFinite-Horizon MDPComputational ComplexityValue IterationPolicy IterationValue Iteration for Finite Horizon MDPsThe Linear Programming ApproachDual LPSample Complexity and Sampling ModelsBonus: Advantages and The Performance Difference Lemma

Overview

This is my note for Chapter 1 of Reinforcement Learning Theory.

Markov Decision Process

Discounted (Infinite-Horizon) MDP

Remarks: 1. This is why it is called discounted MDP. 2. I assume it works like how eigenvalue defines the smoothness for an RKHS?

objective, policies, and values

trajectory

Remarks: 1. It goes like state->action->reward->state->..., and each state is a sample. 2. Sort of like a filtration for a stochastic process

policy

Remarks: 1.

value

which is bounded by

Similarly, action-value (Q-value)

which is also bounded by

Goal: find optimal policy given starting state

Bellman Consistency Equations for Stationary Policies

Lemma 1.4. Suppose that

Proof:

It is helpful to view

Remarks: This is straightforward since a function is in some sense an infinite dimensional vector where each point is a coordinate.

We also will define

Remarks:

In particular, for deterministic policies, we have:

With this notation, it is straightforward to verify

Proof: Notice that

Thus, we have

Also, note that

Corollary 1.5. Suppose that

where

Proof: we need to show that

To see that the

which implies

Lemma 1.6. We have that

so we can view the

Proof: we need to show

Thus, for the element at

For the LHS, we have

where in the second equation we use the Chapman-Kolmogorov equation. Thus the proof is completed by that

Bellman Optimality Equations

There exists a stationary and deterministic policy that simultaneously maximizes

Theorem 1.7. Let

which is finite since

There exists a stationary and deterministic policy

We refer to such a

Proof at P9 of the book.

Remarks: The optimal policy used in the proof is

Theorem 1.8 (Bellman optimality equations). We say that a vector

For any

Proof at P10 of the book.

Notice that

Remarks: Here more notations are introduced:

greedy policy:

The Bellman optimality operator

This allows us to rewrite the Bellman optimality equation in the concise form:

and, so, the previous theorem states that

Remarks: The equivalent form in V can be written as:

where V is a vector (It is straightforward to verify since

The two theorems basically proves that

finding an optimal policy = finding an optimal deterministic and stationary policy

an optimal deterministic and stationary policy is a greedy policy

Finite-Horizon MDP

Changes:

A time-dependent reward function

A integer

Theorem 1.9.(Bellman optimality equations) Define

where the sup is over all non-stationary and randomized policies. Suppose that

Furthermore,

Proof: The flavor of this proof is similar to the infinite-horizon case.

First note that theorem 1.7 also applies to the finite horizon, though the stationary and deterministic

Likewise, we define

So we only need to show that

which follows the exact same proof as the infinite-horizon MDP with the use of an optimal deterministic policy

The reverse is highly similar as well.

Overall, the finite MDP is O(H) larger than the infinite one.

Computational Complexity

Suppose that

Remarks: For computational time, there are some ''standards'' in optimization that are not mentioned here, such as what exactly is

Value Iteration

Q-value iteration: starting at some

Lemma 1.10. (contraction) For any two vectors

Proof at P13 of the book.

Lemma 1.11. (Q-Error Amplification)) For any vector

where

Proof at P14 of the book.

Theorem 1.12.(Q-value iteration convergence). Set

Let

It is actually a corollary of lemma 1.10 and 1.11 and that

Remarks: Setting

Policy Iteration

The policy iteration algorithm, for discounted MDPs, starts from an arbitrary policy

Policy evaluation. Compute

Policy improvement. Update the policy:

In each iteration, we compute the Q-value function of

Remarks: 0.2 is that

Lemma 1.13. We have that.

Proof at P15 of the book.

Remarks:

Theorem 1.14.(Policy iteration convergence). Let

Proof: Notice that

Remarks: Note that PI and VI have the same convergence rate for

PI can be strongly poly due to some analysis. (The intuition is that police is finite (

Value Iteration for Finite Horizon MDPs

Let us now specify the value iteration algorithm for finite-horizon MDPs. For the finize-horizon setting, it turns out that the analogues of value iteration and policy iteration lead to identical algorithms. The value iteration algorithm is specified as follows:

Set

For

By Theorem 1.9, it follows that

Remarks: 1 is just a notation for simplicity, and there is a typo in 2 in the book.

The Linear Programming Approach

VI and PI are not fully polynomial time algos due to dependence on

By the Bellman optimality equation (with the V form), we have

which gives

Therefore the LP is

or equivalently

Conceptually, LP provides a cool poly time algo.

Comments from the slides:

VI is best thought of as a fixed point algorithm

Pl is equivalent to a (block) simplex algorithm

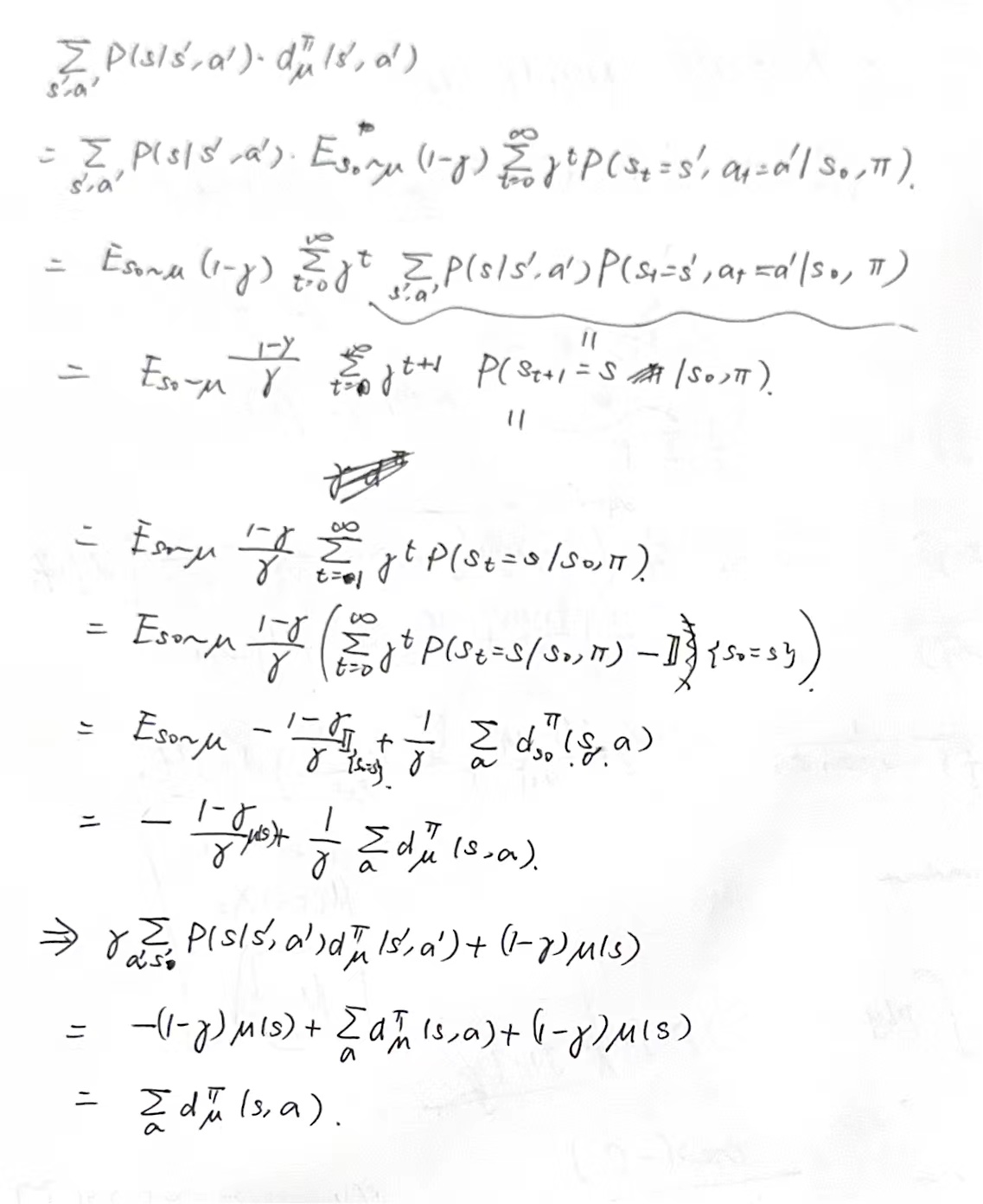

Dual LP

For a fixed (possibly stochastic) policy

where

for a distribution

Remarks: Lemma 1.6 gives

Thus, actually we have

and

It is straightforward to verify that

Remarks: Simply we have

Let us define the state-action polytope as follows:

We now see that this set precisely characterizes all state-action visitation distributions.

Proposition 1.15. We have that

With respect the variables

If

is an optimal policy. An alternative optimal policy is

Sample Complexity and Sampling Models

we are interested understanding the number of samples required to find a near optimal policy, i.e. the sample complexity.

A generative model provides us with a sample

The offline RL setting. The offline RL setting is where the agent has access to an offline dataset, say generated under some policy (or a collection of policies). In the simplest of these settings, we may assume our dataset is of the form

Bonus: Advantages and The Performance Difference Lemma

The advantage

Note that:

for all state-action pairs.

Analogous to the state-action visitation distribution (see Equation 0.8), we can define a visitation measure over jus the states. When clear from context, we will overload notation and also denote this distribution by

Here,

for a distribution

Remarks: In Equation 0.8., we define

Lemma 1.16.(The performance difference lemma) For all policies

Proof at P19 of the book